In 1996, Eve Ensler’s new work The Vagina Monologues opened, and with it began a movement. At the crux of the V-Day movement is a push to heighten the visibility in the public eye of women’s issues both in daily life and in extraordinary circumstances in order to help bring an end to violence against women. Despite the vitality, skill and bravery of the initial work, the movement has attracted criticism from all sides, with hard-line feminists sometimes renouncing the work, and mainstream media sources accusing it of being lewd and unnecessarily shocking. Ensler continues to drive the movement and tirelessly raise awareness of its key issues.

In the introduction to the V-Day edition of the play, Ensler states that she never intended to become the “vagina lady”. Ensler continues to write and create new works, but The Vagina Monologues and the resulting V-Day movement to end violence against women have become Ensler’s life’s work in her dual capacities as playwright and activist.

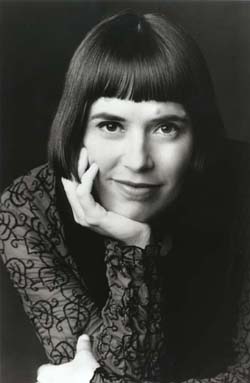

On Monday of this week, I was fortunate enough to attend a workshop with Ensler. At 10am, a group of about twenty playwrights, directors and performers gathered at the Sydney Theatre, ready to soak up as much of Ensler’s energy and wisdom as we could. After introductions were done, Eve explained to us that the workshop today would focus on the art of the monologue, and that we would each be asked to write something quick about a scar on our body and how we received it. These would then be shared and discussed with the group.

As the conversation flowed and one story after another was shared, it became very clear how Ensler has managed to find and nurture so many amazing stories. She’s a warm, accepting and engaged presence, and made us all feel at ease to share what we needed to share. She allowed the group to come to its own realisations through conversation, and when giving direct advice was clear and expressive in equal measure.

Ensler is of course an extreme case, and has truly both earned and embraced her “vagina lady” title. But I think it is important to reflect on such a title. Ensler isn’t just a brilliant teller of women’s stories. She’s a brilliant storyteller. And many women playwrights who aren’t striving so specifically to write for women, about women, can be labeled as “women’s writers” too easily. As always, it’s important to remember that women are just as capable of writing male stories as are men of writing female ones. But beyond that, it’s vital that we remember that a woman playwright writing female characters by no means excludes a male audience. If anything, this is important work for men to see. One of the many things that the theatre is in the business of providing is a window into an experience we would not be privileged with in our day-to-day lives. In everything from a play that incidentally has an all female cast to something as specifically feminine as The Vagina Monologues, a female writer, creative team, character or story should never be viewed as niche. It’s an old adage but it remains true – half of our world is female; so too should be half of our stories, and half of our audiences for those stories.

For more thoughts on the status of women playwrights in Australia, come along to the Playwriting Festival for our panel On Women, featuring leading female playwrights such as Debra Oswald (The Peach Season, Mr. Bailey’s Minder), Jane Bodie (Out of Me, A Single Act) and Van Badham (Black Hands / Dead Section).