In Tom Stoppard’s play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Guildenstern declares that:

In Tom Stoppard’s play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Guildenstern declares that:

‘All your life you live so close to the truth it becomes a permanent blur in the corner of your eye, and when something nudges it into outline it is like being ambushed by a grotesque’.

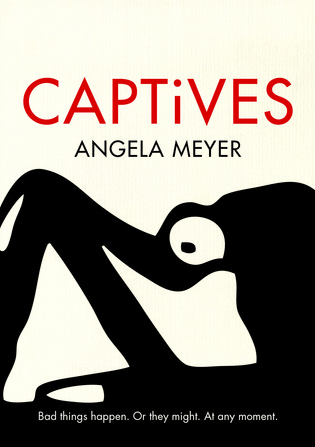

And so it is with the stories in Angela Meyer’s Captives, a tiny yet multitudinous collection of flash fictions that constantly defies its brevity. The stories are arranged under seven different headings, such as ‘On/Off’, ‘Up/Down’, ‘Here/There’, and the wonderfully final ‘Until’, all implying some sense of opposition between two extremes.

In some stories this struggle is clear throughout, such as ‘Glitch’ where Meyer depicts a character longing to find respite from the incessant voices in her head, only to stumble on unexpected silence. So too in ‘Thirteen tiles’, where the protagonist (antagonist?) spends his time locked in a room counting tiles and the time it will take for his corpse to be discovered. The conflict in these stories is palpable, between one place and another, one memory and one reality, between desire and frustration. The characters and the stories are captives of the flash-fiction form, but are in a constant state of trying to break out.

Meyer’s stories breach the confines of the page. Despite the length — some no more than a paragraph — they suggest entire realities that lay submerged beneath the consciousness of the page. Characters portray entire histories in the brief moments they have — the narrator and her boyfriend’s brother in ‘Like another time’ seem to wrestle with a depth to their lives that is just beyond their reach.

Many of the stories in Captives are momentary, but that is the nature of flash fiction. When it works, as it does in Meyer’s hands, it is because this kind of writing is more than the sum of its parts. Most of these stories can be absorbed in one glance, and even the longer ones like ‘Amsterdam’ and ‘Nineteen’ offer us the possibility that these brief narratives could be a beginning, or a middle, or the ending of something much larger. The reader is rewarded for their attention, and for their second and third reads.

Captives is longer than it is short, deeper than its slim volume suggests, and all of Meyer’s stories refuse to be bound by their short forms. Some take on historical fiction, others stroll assuredly into science fiction and beyond — such as the wonderfully melancholic ‘My sweetheart saw a child’s face in the train window’.

Throughout the collection, the macabre, mundane and melodramatic are all held up alongside one another in contrast and companionship, as each story tries its hardest to signal grotesque truths about its inner world to us, the infinitely rewarded reader.

Craig Hildebrand-Burke is a writer and teacher from Melbourne. His writing can be found at craighildebrandburke.com.