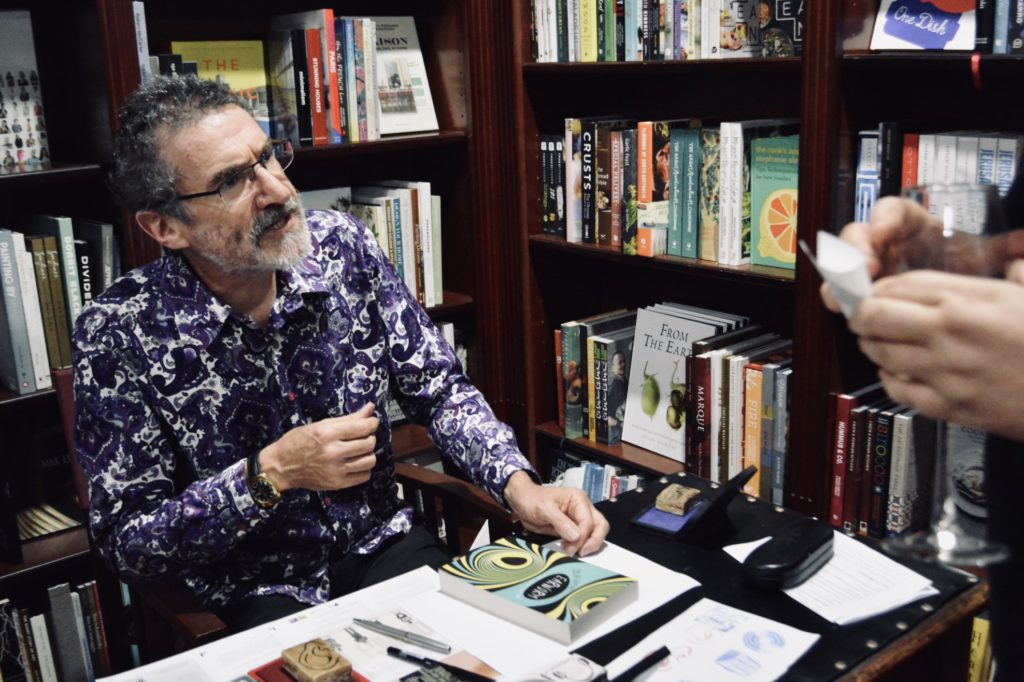

Each month we shine our spotlight on a member of the Writing NSW community to learn more about their writing journey, achievements and inspirations. This month we spoke with Colin Varney, author of the tragicomic novel Earworm.

Colin Varney is a Sydney-based writer and musician whose first novel Earworm was published by Margaret River Press in 2018. His short fiction has been published in Meanjin, Kill Your Darlings, Island and Southerly, while satirical pieces and articles have appeared in Slackjaw, The Lifted Brow, The Adelaide Review and Tasmanian Times.

Our membership intern, Alina Haque, spoke with Colin about his unorthodox storytelling, the challenges of navigating Australia through music, and how he succeeded in writing his first novel.

Congratulations on publishing your first novel! Tell us a bit about Earworm.

Many thanks! Earworm is the tale of Nicole, a young woman who uncovers devastating family secrets that are inextricably tied to the 90’s pop song ‘Empty Fairground’. When she flees to another city in search of answers, her mother and boyfriend race against time to locate her. In a twist, these incidents are narrated by ‘Empty Fairground’, the love song that reverberates within the minds of the major characters, nuzzling against their thoughts, dreams and aspirations. The narrator becomes a character in itself, sifting events through a unique lens.

Earworm eschews conventional linear storytelling. What drew you towards this highly experimental style of writing that plays with the fluidity of memory and time?

The inspiration for Earworm came from a review for Great House by Nicole Krauss in which a desk plays such a decisive role that it essentially becomes a protagonist. I believed that I could go one better and create a character that was both non-human and immaterial, and lit on the notion of using a song.

Songs themselves tend to be non-linear. They work on us by exploiting time, forging links to an era, or by conjuring an associated memory. If I was to be true to my narrator, it was important to follow these trails through memory and history.

Nicole’s sense of self is predicated on family myth and cultural influences, so the past presses upon her. Memory is so crucial to identity that it constantly prevails within us, ensuring the past is a vital component of the present. I wanted to suggest that illusion and delusion are also part of who we are. It is telling that the narrator has difficulty distinguishing memory from fantasy.

What were the challenges in relaying a true-to-life Australian setting across the multiple time periods this novel traverses?

Earworm takes place in Adelaide, where I was raised, and Hobart, where it was written. I wanted to give a feel of Adelaide’s harsh suburban sprawl and a sense of its merciless climate moulding its denizens. Hobart has a gentler pace. Life there is regulated by the sluggish tides of the Derwent and the contemplative frown of the mountain. The colder weather and confined island setting also encourages a strong sense of community.

Negotiating the time shifts was more problematic. Because the narrator juggles with memory, I often found myself attempting to tell two incidents simultaneously: the present and the recollection that buoys it. I was able to employ some of the tricks that nostalgia plays on us by superimposing a golden aura over fondly remembered events.

You’ve spent much of your life immersed in music. How have your experiences on the Australian gig circuit shaped Earworm?

Adelaide has long had a resilient underground music scene. I was in a clutch of bands that eschewed cover versions (and therefore audiences) for original material. It was a joy to watch my friends cobbling tunes together, producing uncompromising and often unclassifiable mutant music. It had a profound effect on my fiction: I found myself increasingly pursuing musical themes, before attempting to give voice to music itself via Earworm.

Band life was invaluable in providing background for the songsmiths that created “Empty Fairground”. The language became heightened and rhythmic, drenched in florid imagery pilfered from pop lyrics. Musical metaphors and in-jokes began to proliferate: when referring to silence my narrator invokes John Cage’s “4’33”” and the black dog of depression conflates with the “Black Dog” of Led Zeppelin.

Despite this, it was necessary to research the more technical side of music and genres where I lacked knowledge. One of my characters is an opera buff and another a jazz fan, and these were both areas where I needed to bolster my expertise.

The 90’s hit ‘Empty Fairground’ worms its way into the lives of characters that reveal changes in Australian society across time. Are love songs reliable narrators?

Love songs are created to celebrate heightened moments that possess and enthral, completely overwhelming us with ecstasy or sorrow (sometimes both, simultaneously). My narrator is a non-human entity that considers the rush of romantic love to be the lynchpin of the human condition. It therefore has an off-kilter perspective on the complexities and banalities of life. It struggles to understand filial love and considers “relationships” to be craven compromise. It battles to comprehend Nicole, while arrogantly believing it knows people better than they know themselves. Throughout Earworm, this extremely subjective and unreliable narrator is striving towards a revelation of what it means to be human.

Some of my favourite sections of the novel are when the narrator convincingly prosecutes an opinion that I personally find disturbing. For me, that is when my storyteller becomes independent and I become a kind of literary empty nester.

Any words of advice for writers embarking on their first novel?

Re-writing is the most powerful tool any writer has. Be prepared to kill your darlings. No matter how enamoured you are with a concept, character or paragraph, be ruthless in your culling if it doesn’t fit. Consider a creative writing course or workshop. At their best, they offer appraisal and impose discipline. Your mentor may also have knowledge of the industry and be able to recommend a publisher.

Any writing projects on the horizon?

The challenge of a sophomore novel is insistent and I have recently succumbed to it, jotting notes. Naturally, the new project involves music. It may evolve into a kind of comedy thriller. At this stage it also has an unusual storyteller, but the voice will not be as front-and-centre as the impudent narrator of Earworm.

*

About the Author

Colin Varney’s aversion to drummer jokes developed while playing percussion and composing lyrics for Adelaide underground bands. His work in children’s television includes scripting for a bodiless face (Mulligrubs) and a pants-shy bear (Here’s Humphrey). His short fiction has been published in Meanjin, Kill Your Darlings, Island and Southerly, while satire and articles have appeared in Slackjaw, The Lifted Brow, The Adelaide Review and Tasmanian Times. He completed a Masters’ in Creative Writing at the University of Tasmania, under the auspices of Danielle Wood (The Alphabet of Light and Dark). The result was the tragicomic novel Earworm, published by Margaret River Press in 2018.