Jo Riccioni was born in the UK to an Italian father and English mother. She has a Masters in English from Leeds University and worked in Singapore and Paris before settling in Sydney’s Northern Beaches.

Jo Riccioni was born in the UK to an Italian father and English mother. She has a Masters in English from Leeds University and worked in Singapore and Paris before settling in Sydney’s Northern Beaches.

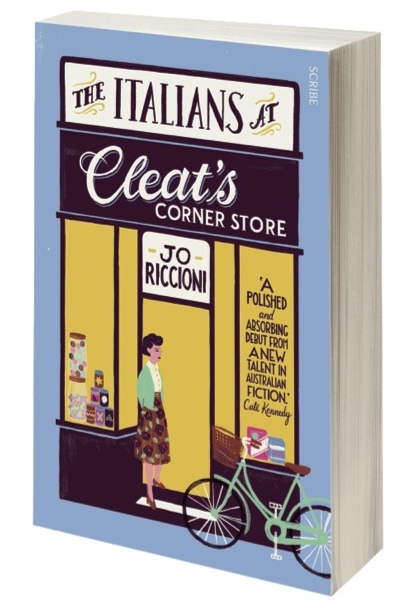

Her short stories have been read on the BBC and National Radio and published in the UK, the US and Australia, including The Best Australian Stories 2012 and 2011. Her story ‘Can’t Take the Country Out of the Boy’ has been optioned for a short film. The Italians at Cleat’s Corner Store is her first novel.

Jo made her first forays into writing after courses at the NSW Writers’ Centre — one with Sue Woolfe and another with Mark Mordue back in 2002-2003 — and she still comes to courses, the most recent being last year’s Open Access Seminar. You can read more of her work here.

Jo will be featured during the Late Night Library series, ‘First Timers’ on 12 November 8-9pm, Haymarket Library. Book online or call (02) 9265 9333.

Author Interview

Has a particular book or event influenced your decision to become a writer and why?

The decision to write came relatively late in life for me, but I’ve always been a greedy consumer of stories in any form: novels, short fiction, plays, film, TV. I think my first attempts to write my own fiction were really born of boredom and frustration: I was a new mum with an academic background and a corporate job on hold, a foreigner with few friends where I lived, and a brain that felt like it was slowly turning to mashed pumpkin.

What was the turning point in your career? How did you get your first big break?

Placing second in The Age short story competition made me sit up and think someone might actually want to read what I wrote. Then I was selected by Cate Kennedy for Best Australian Stories 2010 and later her editor, Aviva Tuffield, signed the early chapters of my novel.

You were awarded a Varuna Fellowship and a residency, how has this assisted your writing career?

For me, the bottom line with Varuna residencies is that they get words on paper — lots and lots of words (which is the best kind of ‘career’ help for a slow writer like me). At Varuna, you can write all night and read all day in your pyjamas if you want to, and there will still be food on the table and milk in the fridge. Back home, your children may have redecorated the lounge room in Crayola red and given the dog a new ‘haircut’, but for those weeks at Varuna there’s nothing you can do about it: you’ve got a chance at the Ivory Tower and you’ve got to tap it for all it’s worth. Varuna also gave me the opportunity to connect with other writers, and some of them have become generous friends and ‘co-workers’ in a solitary profession.

Could you tell us a little about your writing technique: is your routine rigid or relaxed? Where do you look for inspiration?

I’d love my routine to be rigid, but I know it’s way too relaxed at times and I give myself grief over it. It’s a constant struggle not to allow other demands to come before the writing and, when I’m working on raw material, I find the only way to get around that is to start the day when it’s still dark and write for a couple of hours before the rest of my life stakes its claim. I find the afternoons or evenings are better for editorial work — my brain seems to become more critical the more engaged I am with the world. I usually find inspiration when I don’t have a notebook to hand. I jot things on my phone’s Notes app, which junks up my email with cryptic musings that later make me panic I’ve been hacked. I get ideas when I’m falling asleep or waking up and subsequently, at my desk, I’m always trying to catch the ‘fiction that got away’.

How did the idea for The Italians at Cleat’s Corner Store take shape?

My Italian grandfather had been a prisoner of war in England. When I was 16 I had to do a school history project on memories of the War, so I pinned him down with lots of questions about his experiences. He was always reluctant to speak about his capture and internment or his early Fascist sympathies, so of course that was what I became fascinated with. I’d also spent most of my summers in Italy as a child listening to the rest of my family’s memories of the War in Lazio and their experiences as immigrants in England in the late 40s, settling on the farm where Nonno had been a prisoner. I think I always knew there was a novel in their stories. I just didn’t know whether I’d be the one writing it. It was only decades later, when I’d just had my first child, that I started recording their memories, starting some serious research and dabbling with early characters and scenes.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have been given?

I’ve taken note of lots of really great advice by many writers I admire and [have] been taught by, but the thing that sticks with me is this corny business quote from Jim Rohn: ‘Motivation gets you started. Habit is what keeps you going’. It’s written on the wall of the gym I go to. Don’t laugh about the ‘gym’ part! Stephen King’s ‘butt glue’ may be what you need to write a novel, but you’ll also need a good physio if you ignore your body. I’ve never had a problem making fitness a habit, but I often have a problem making writing one. I try to remind myself that the discipline behind both is not that different: I’m miserable when I don’t exercise, so I exercise; I’m miserable when I don’t write … so just write. That’s the theory anyway. I try hard not to think about it too much, just make it one of my habits.

Excerpt from The Italians at Cleat’s Corner Store

Excerpt from The Italians at Cleat’s Corner Store

Connie rounded the corner of the rise, still engrossed with the events of the evening. At the crest of the hill, though, habit made her stop to look out at the gamekeeper’s cottage. The sun had sunk below the clouds, and the barley and wheat rolling before her shivered in the breeze like the skin of some vast animal. She felt the shudder of it in her own skin and was about to cycle away when she caught sight of a figure at the edge of the spinney.

At first she thought it was Fossett, off to the Green Man after his rounds checking the young pheasants. But soon she made out the broad shoulders of Lucio Onorati, bent over, examining something in the rough before the trees. When he stood up, she saw in his outstretched fist an animal held by the hind legs. Squinting, she made out the sleek skin, the distended belly of Mrs Repton’s pregnant Siamese. It twitched, like one length of overworked muscle, and the wind over the ridge teased its fur, the colour of fine sand, its darker undercoat glimpsed like a secret. She watched him run his free hand slowly upwards from the neck to the tail, and the cat seemed to settle. She thought of the press of spine under fur, the stretched sinew of its body, the green eyes glazing as they would when she stroked it. For an instant, the shape of them seemed one and the same to her, camouflaged by the silence and the fading light.

The cuff of his hand was quick and blunt, strangely unsurprising when it came. She imagined the muted crack of bone, like a twig under leaf litter when she walked in the spinney. He descended the fallow towards the brook, the cat limp across his back, nothing more than quarry now in one practised blow of his hand. She gripped at the handlebars of her bike, feeling disconnected somehow, as if she was the foreigner in her own world, not him. But after a while he was nothing more than a shadow, swallowed up by the huddle of sombre trees at the brook’s edge.

You can find out more about Jo’s work here.