Loretta grew up in Ballarat, immersed in the story of the famous Eureka Stockade. Time spent as a history researcher and writer at Melbourne University boosted her interest in little-known snippets of Australian history. She is also a lawyer and has published many legal articles.

Loretta grew up in Ballarat, immersed in the story of the famous Eureka Stockade. Time spent as a history researcher and writer at Melbourne University boosted her interest in little-known snippets of Australian history. She is also a lawyer and has published many legal articles.

Loretta’s other publications include a picture book for children, Flying South, which was published by Harper Collins, and a regular fortnightly column reviewing books and movies for Medical Observer. She has published light verse and humorous articles in a number of publications including the Sydney Morning Herald and a Penguin anthology.

Loretta divides her time between the farmers’ markets in Albury and the coffee shops in Sydney, and is now writing full time and actively involved in the New South Wales Writers Centre. You can read more about her work here.

Interview

When did you first hear about the fantastic idea for your book, set in the 1930s, Stand Up and Cheer?

When my family first moved to Albury in the 80’s I was fascinated by the old DC 2 plane called the Uiver that was sited near the airport. I was struck by its odd name, wondering what it meant and how you’d say the name. Uiver is the Dutch word for stork and it turns out there are various ways of pronouncing it: people in Albury nowadays call it the Ivor, older residents who helped rescue the Uiver recall they referred to it back then as the Weaver, and Dutch friends insist it should be pronounced Oever. But everyone agrees [that] however it’s pronounced it’s a great story that’s now one of the star attractions at the great LibraryMuseum in Albury.

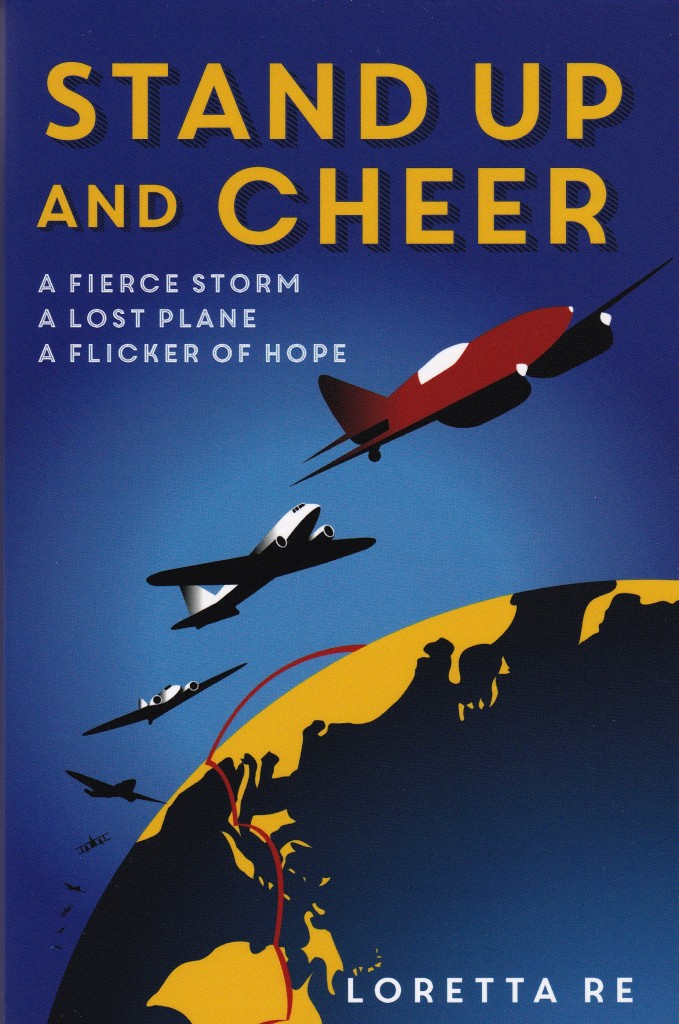

The Uiver was the biggest plane in the world when it was built in the US in 1934. KLM then purchased it to fly on its regular mail route between the Netherlands and its colony in the East Indies. For the inaugural flight, KLM decided to enter the Uiver in the Great Centenary Air Race by extending its regular route to start in London with the other competitors then continuing beyond Batavia to the end of the race at the Flemington racecourse. Despite having to drop off mail at various ports en route the Uiver made fantastic time thanks to the precision of the pilot Captain Dirk Parmentier who held the world night flying record.

On the last leg of the flight between Queensland and Melbourne the plane flew into a terrifying electrical storm in the middle of the night and tracked off course, lost over Albury. With fuel running low, the crew believed they were doomed, even holding a private religious service in the cockpit. How Albury people rallied together to save the plane, its crew and passengers has become part of aviation history, and provides the climax to the story of my hero, ten-year-old Jack.

How much research did you need to do to make this story come alive, and did you have a system?

I did an enormous amount of research over a period of two years or more. I visited the LibraryMuseum repeatedly and saw their fabulous display of films, photographs and gifts to the city, including a solid silver model of the plane from Queen Wilhelmina the reigning monarch at the time. Hours were also spent on Trove sifting through old newspapers and contemporary documents.

I also spoke to the son of the local ABC radio announcer in the 30s, who remembered the night very well, and I knew then I had the perfect model for my hero. A Dutch friend, Chris, very kindly spent his holiday tramping the streets of Holland until he found a copy of Captain Parmentier’s memoir in an old bookshop, and then he translated it into English for me. That was a wonderful find because it revealed how terrifying it was for the crew on board when they were lost. And in my turn I tramped the streets of Albury to make sure that the local landmarks I referred to in the book did exist at the time.

I decided to learn about ham radio too, and while researching I stumbled across the Australian Air League, an aviation movement for children still very active today. By a stroke of enormous good luck it was founded in 1934 and I knew immediately that Jack would be a member.

I’m sorry to say that despite working in research for years, my methods are still completely chaotic with scraps of paper everywhere like dots of confetti. So no, I don’t have a great system, although I do have a great sister who very generously sorts out my notes for me. But, you know, it isn’t really the research that makes the story come alive. It’s essential of course, yet at some point you have to forget all the research and enter an imaginary world. I’d say nine tenths of the research never makes it into the book, although it does live in the writer’s mind.

Who has influenced you in your creative writing?

Everyone you’ve ever read influences you I think. Australian writers like Kate Grenville or Thomas Keneally who write historical fiction are towering examples of how it’s done brilliantly, and in children’s historical fiction I loved Morris Gleitzman’s ‘Once, Then, and Now’ series; he’s such a wonderfully versatile writer. And Belinda Murrell writes great stories that are firmly mired in historical fact.

While I was writing the book, Sue Woolfe’s and James Roy’s input was invaluable. James’s course on how to write a YA novel [held at NSW Writers’ Centre] is wonderfully designed and if you take on board his insights you will end up with a finished product that’s richer than it would be otherwise.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have been given?

Quite a while ago I took a writing course with Kate Grenville, at Sydney University, who said to me, ‘You just need to go away and write’. Coming from her, that was extremely powerful, and it stayed with me. It showed faith that I had the potential to be a writer and it implicitly said: having a dream is important, but action is absolutely crucial. Writing is a hard grind, and it’s very tempting to throw in a novel mid-course, but you have to keep working away until you’re satisfied – or sometimes, until your editor is.

What are you reading at the moment?

I’ve just finished Michelle De Kretzer’s Questions of Travel, and thought it was absolutely fabulous. She manages to channel Christina Stead and Shirley Hazzard, while maintaining her own voice and creating a world that is so easy to recognise as modern Sydney and Sri Lanka. But it’s a very humbling book, and makes me wonder why I even bother to write at all.

I’ve also started J K Rowling’s The Casual Vacancy, because I’m intrigued to see how the author makes the transition from writing for children to writing for adults. Now I’m immersed in it I’m starting to remember what storytellers have known for centuries – that the great children’s stories are really for adults. That’s the downside to becoming a writer. You never read a novel for pure enjoyment again!

Your character, 10-year-old Jack, is fascinated by planes. Do you share any of that fascination?

No, not really, although Jack’s quest to save Cherry Ripe wrappers to win a trip to the air race was modelled on my own childhood when we collected soft drink bottle tops in pursuit of one of two prizes: a sewing box or a model plane. I remember definitely thinking the plane had it all over the sewing box!

Extract from Stand Up and Cheer

Extract from Stand Up and Cheer

A beam of light shines on the tussocks beyond the white railing.

‘Wow,’ Arnie and I say together.

A startled rabbit hops away into the tall grass.

‘And watch this,’ Dad says with a chuckle, pleased that we’re so impressed. He flicks the switch again and the headlights go off. Then he gives us another burst of yellow light.

‘And … I can give morse signals,’ he tells us with relish.

‘What’s morse signals, Dad?’ I ask.

‘It’s a way of sending a message without words.’

I’m dazzled by the idea. ‘How can you talk without words?’

‘Pilots do it sometimes. They tap out sounds over the radio. Or they can send out little pips of light. Watch.’

He flashes the lights again. ‘Two dits, one dah. Quick, quick, slow,’ he says like a dancing teacher. ‘That’s a U,’ he adds.

I can hardly believe it. A secret language without words. Without letters. A language that pilots all know. I want to learn more. ‘Will they use it in the Centenary Air Race, Dad?’

‘Course,’ he says. ‘At least, the big planes will. That’s how they’ll contact the aerodromes before landing. To check the weather. Check the layout of the landing strip. So they know it’s safe to land.’

And it’s like the sky has opened up and shown me all the stars in the universe. I have to learn morse code. I have to know all about this special pilots’ language.