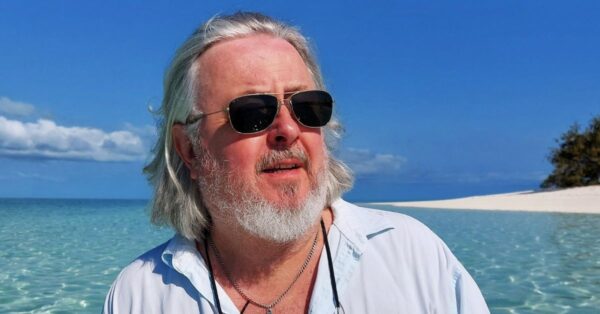

In our Spotlight On series, we chat with a member of the Writing NSW community to celebrate their success and learn more about their writing practice. This month we put the spotlight on Jonathan Cant, award-winning writer, poet, and musician. Jonathan spoke with our Administration Officer, Nevenya Cameron, about the importance of poetic form, nature in his writing, and navigating the Australian publishing landscape.

You recently won the Banjo Patterson Writing Award for Contemporary Poetry for your poem ‘Thunderstorm at Newton Boyd’. Tell us about your connection to rural Australia and how you represent this in your poetry.

My earliest rural connection comes from both my parents growing up in regional towns before meeting when they moved to Brisbane. So, my school holidays were spent with grandparents either in the country or on the coast. Those positive memories stayed with me and helped inform some of my later interests.

I also love being on the road—especially in the mountains. In the many years I was focused on things other than writing, I was exploring the country backroads of South East Queensland, New South Wales and North East Victoria, on my own, immersed in landscape photography and/or searching for trout streams to fly-fish. That’s how I found myself travelling the isolated Old Grafton Road which led to writing ‘Thunderstorm at Newton Boyd’.

Sadly, we have a lot of ghost towns and declining communities in rural Australia. For far too long, regional areas have not received the attention, investment, and infrastructure they deserve, and need, to survive.

‘Thunderstorm at Newton Boyd’ combines different forms into one piece. How do you think form contributes to finding meaning in poetry?

‘Thunderstorm…’ is an experiment in form. A fusion of styles. I see it as what might be called a ‘Western haibun’. Unlike Matsuo Bashō’s original Japanese haibun of prose poetry punctuated by haiku tercets, this piece consists of prose poetry interspersed with traditional ballad-like quatrains (not unlike a refrain or chorus in songwriting). So the end result is a kind of haibun hybrid — a ‘haibrid’, perhaps.

My mentor Mark Tredinnick was interested in what I was doing with form here, but felt it needed more content and concrete imagery to ground it with a strong sense of place. Hence the added ‘farmstead’ paragraphs which were based on black and white photos I’d taken of old farm ruins and relics.

With regard to form (and what it lends to poetry nowadays), I still see it as integral. Form can add musicality and a degree of comforting familiarity. And some forms are tailor-made for certain tones and subject matter. I do write free verse, but I want to continue my exploration of form: fusing, subverting, and even modernising them.

Another aspect that drives my work is a desire to combine so-called ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture/language—surprisingly and often within the same poem. It’s my belief that this is one of the ways poetry can regain some of its lost audience. I’d like to see poetry become more accessible (and appealing) to a wider cross-section of the public—irrespective of their circumstances, background, or level of education.

‘Thunderstorm…’ is also a poem about things that cause an initial level of excitement, then lead to disappointment, despair, or even death. Things such as severe storms, the discovery of gold, the onset of the First World War (and the way in which it was pitched to young men as ‘a great adventure’), or even the allure of party drugs such as Fantasy. The latter refers to a tragic event that occurred at an unauthorised music festival near Newton Boyd in 2016, when a young man died of an alleged GHB overdose/interaction.

Much of the imagery in your poetry connects to nature. How does your creative writing practice intersect with the natural world?

As with many writers or artists, my poetry and Nature do ‘intersect’ profoundly—like George and Park Streets meeting at Sydney’s Town Hall. Nature and the arts are my two main pillars, both in life and my work. I’ve always been in awe of Nature. It’s where I find meaning, beauty, and contentment. From an early age, I was fascinated with marine life—and birdlife, especially—and I loved exploring rainforests, mountains, creeks, and tidal rock pools.

As for my writing, yes, Nature is an ever-recurring theme; whether that be in a purely metaphorical sense or when I’m addressing issues such as wildlife conservation, ocean plastics, deforestation, climate change, and sustainability.

Who are your favourite contemporary poets capturing the unique Australian experience?

Judith Beveridge, Mark Tredinnick, Judith Nangala Crispin, Les Wicks, and Tug Dumbly all come to mind as poets who—in their different styles—are especially adept at capturing this country’s unique natural landscape (in nuanced detail) and its human diversity.

You have published in various Australian literary journals during your career. What challenges have you faced navigating the Australian publishing landscape as a poet?

Style and content will always be subjective—and contentious—elements in literature. Not every piece will be ‘the right fit’ for a given contest, publication, or audience. For any writer, rejection just goes with the territory. It’s inevitable. But it can also be instructive and regenerative.

Sometimes a poem just needs to ‘find the right home’. I believe it’s crucial to remain optimistic and never give up on your craft. Be true to your own unique experience: what you know, feel, and wish to communicate—and the manner in which you want to do it.

You have had several successes in poetry competitions during your career. What advice would you give to an emerging poet looking to enter their work in competitions?

The same advice given to me: focus, initially, on sending work to competitions (as opposed to literary journals), because at least they’re judged anonymously. Being placed, shortlisted, or recognised a few times allows you to gradually build confidence, a profile, and an audience—as does reading your work regularly at open mics.

Also, it’s wise to familiarise yourself, if possible, with the competition judge’s own work. That’s not to suggest you should mimic them, but rather that, it’s just realistic to be mindful of the forms, tone, and recurring themes in their poetry. Finally, it’s a no-brainer, but follow all competition rules and guidelines absolutely to the letter; and, if there’s a given theme or prompt, be sure to fully address it when you write, or select, poems to send.

Jonathan Cant is a Sydney-based writer, poet, and musician. He won the 2023 Banjo Paterson Writing Awards for Contemporary Poetry, was Longlisted for the 2023 Fish Poetry Prize and the 2022 Flying Islands Poetry Manuscript Prize, and Commended in the W. B. Yeats Poetry Prize. Jonathan’s poems have appeared in Cordite, Live Encounters, and Otoliths. Over the past two decades, Jonathan has also worked as a copywriter in the advertising and not-for-profit sectors.

Here’s where you can read more Spotlight On.