Writers on Writing is our regular conversation with a writer or industry professional about the writing craft, industry insights, and their own practice. This week, we spoke to Lisa Shanahan about the unique collision of memory and observation that form authentic stories for children.

At what point did you decide you wanted to become a children’s writer?

When I was training to become an actor in my early twenties, I taught drama to a vibrant group of kids out west. During that time, I wrote a play especially for them, and even though it was not brilliant, the joy of those kids on reading it was contagious. It dawned on me then, that perhaps I didn’t want to be an actor after all. Which made sense of why I was spending so much time in the university library, sprawled on the carpet, reading picture books by Bob Graham, Margaret Wild and Libby Gleeson. And so not long after I finished my acting degree, I enrolled in a short six-week writing for children course with the acclaimed writer Libby Gleeson, which was just the best and the most delightful beginning of a long apprenticeship in learning how to become a writer for young people.

You have written many award-winning books for all ages; including picture books, junior fiction, middle-grade fiction and a novel for teenagers. What is one of the main differences between writing picture books and middle-grade fiction?

When I’m writing a picture book, a great deal of my energy is spent in winnowing the text, in distilling it right down, so that the text is tight and muscular, saying all that needs to be said with poetic power, whilst leaving enough room for the illustrator to tell their side of the story. In picture books, the vivid rendering of the setting is largely carried by the illustrations and it’s important for a writer not to stampede over the work that rightly belongs to the illustrator.

But in middle-grade and teenage fiction, it’s the opposite. The responsibility for the setting wholly rests with the writer, and these novels often rise or fall depending on a writer’s savvy skill to create a believable world. Rather than just winnowing a text, a writer needs to learn the capacity to billow it, in just the right places—capturing perfectly observed, sensuous detail, whilst weaving it deftly through the action of the story.

When I was writing The Grand Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler, my middle-grade novel, I wanted young readers to come away feeling like they were living in a tent alongside Henry. I wanted young readers to smell the freshly baked bread drifting from the bakery across the road, to feel the sticky dampness of the salty sea air on their skin, to hear the mournful cries of the corellas as they settled in to roost for the night. I wanted the world of Yelonga to feel as intensely alive to middle-grade readers as their own homes felt to them.

Despite some differences, writing picture books and novels for middle-graders share much in common, including the importance of creating vivid characters, with fiercely true, compelling voices.

Do you test out your writing on your own children, or on other young people in your life?

I certainly have shared my stories with my own children over the years but I don’t believe that this is the critical factor in a story’s success. I think it’s more important that writers learn how to harness their own memories of what it was like to be a child, alongside the consistent sharpening of their powers of observation.

Many of my picture books have come out of an intricate collision of memory and observation, including Hark, It’s Me, Ruby Lee! (ill. Binny Talib) This book features a small lively girl, who is desperate to be chosen as the classroom messenger but who is constantly defeated by her own overactive imagination. The idea for this story arose out of a school visit, where I saw a small girl fail to deliver a message for her teacher-librarian, in spectacular fashion. That little moment sparked an emotional pinprick—the memory of my own childhood desperation to please in the classroom and the hot fizz of shame when it all went pear-shaped. The pang I felt for that little girl lingered for some years, until I finally wrote a story where the goodness of an overactive imagination was roundly vindicated in the final pages.

How can we develop consistency in incorporating humour and heart into our writing, which often feels challenging to achieve?

Humour is foundational to encouraging true connection and it can definitely be a challenge to capture the laugh-out-loud jumbly nature of life, alongside the sometimes bittersweet ache of being alive, with sincere consistency. So much of being able to weave humour and heart into our writing is learning how to become attuned. Attuned to the ridiculous, the bittersweet, and the uproarious moments of life.

I carry a journal wherever I go and I’m always on the look-out for moments that have a promising zing. I remember once asking my Star Wars-obsessed, four-year-old son to go and help his brothers tidy up their bedroom, and the way he turned towards me, saying, ‘No! I cannot! It is not my destiny!’ Now, some of the funny moments I observe go on to become actual stories, but the moments that don’t are just as important as the ones that do, because in all kinds of ways, all of these moments are training me in how to see and listen, with greater texture and depth.

In Hello World, the reader sees the world through the eyes of a toddler. When tasked with writing from younger perspectives, how do you maintain an authentic voice?

When I was writing Hello World, I was pondering the significance of those small daily moments in the life of a toddler; the waking up, the kisses, the hugs, the glitter and the glue, the trips to school, the cloud-watching, bath time and the stories on a big person’s lap before bedtime. My acting training has certainly been helpful in learning how to create and shape the individual rhythms and cadences of any voice. But learning how to listen to children around me, and learning how to listen deeply to the child I once was, has taught me just as much. It’s out of this clash of the real and the remembered, that an authentic voice often arises.

I will say that the other essential task to maintaining an authentic voice, particularly in a picture book text, is learning to read it out loud in draft form. Picture books are spoken texts, almost theatrical events, and they’re designed to be read out loud, over and over again. For some reason, the reading out loud process is often neglected. It can be really helpful to have multiple people read the text out loud too, so that we hear the words we know so well afresh for the first time, which can help expose the unfortunate chinks and the dissonances that are a natural part of any work in formation.

What are some great children’s books you’ve recently read that are fierce, funny and/or true?

Some of the children’s books that I have particularly loved lately, that capture so tenderly what it means to be a kid, to be a human, and to be alive in this beautifully complicated world, with a fierce, and at times, a funny truthfulness, include;

Picture Books

The Truck Cat by Deborah Frenkel & Danny Snell (Hardie Grant Publishing)

My Friend Fred by Frances Watts & A. Yi (Allen & Unwin)

Volcano by Claire Saxby & Jess Rackyleft (Allen & Unwin)

Happy All Over by Emma Quay (ABC Books)

Three Dresses by Wanda Gibson (UQP)

We Live in a Bus by David Petzold (Thames & Hudson)

Junior Fiction/Middle Grade

The Midwatch by Judith Rossell (Hardie Grant Publishing)

Hazel’s Treehouse by Zanni Louise & Judy Watson (Walker Books Australia)

Leo & Ralph by Peter Carnavas (UQP)

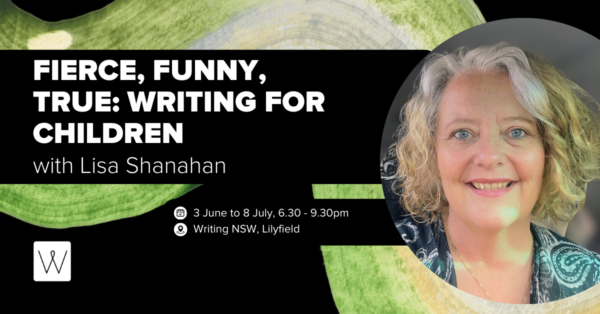

Lisa Shanahan is an award-winning writer of picture books and novels for young people. Some of her funny, heartfelt books include The Grand, Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler, which received the 2017 Queensland Literary Award for Children’s Fiction, the 2018 Speech Pathology Book of the Year for 8–12-year-olds and was shortlisted in the 2018 CBCA Book of the Year Award for Younger Readers. Her picture book, Bear and Chook by the Sea (ill. Emma Quay) won the CBCA Book of the Year for Early Childhood in 2010 and Hark, It’s Me, Ruby Lee! (ill. Binny Talib) was a 2018 CBCA Honour Book of the Year for Early Childhood and was also shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for Children’s Fiction. Her novel for teenagers, My Big Birkett was published to critical acclaim in Australia, where it was shortlisted for the 2007 CBCA Book of the Year for Older Readers and in the United States, where it was a 2008 New York Public Library Best Book for the Teen Age. Her most recent picture book, Hello World (ill. Leila Rudge) won the 2022 Speech Pathology Book of the Year for Birth-3-year-olds. Lisa relishes writing for young people and is incredibly grateful to be doing what she loves.

Join Lisa Shanahan for her course, Fierce, Funny, True: Writing for Children, 6 x Tuesdays, 6:30-9:30pm: 3, 10, 17, 24 June, 1, 8 July at Writing NSW.

If you want to be the first to read great advice, prompts and inspiration from our incredible tutors, subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter Newsbite.

More from Writing NSW

Check out our full range of writing courses in Sydney, our online writing courses and our feedback programs to see how we can help you on your creative writing journey. Find out about our grants and prizes, as well as writing groups across NSW, and sign up to our weekly newsletter for writing events, opportunities and giveaways.