FALLING UNDER THE SPELL

It has become cool to be a sociopath. At least that’s what fiction is telling us. If the roaring success of Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal of Sherlock Holmes was anything to go by, being a ‘high-functioning sociopath’ will not only get you the girls, the money and the international fame, but it’s a great way to solve crime, catch killers and save the world, all in time for biccies and tea.

In my line of work as a crime fiction author, I keep my eye on crime in the real world, and the work of people with this condition in the news, in true crime podcasts and in true crime books. I need to get into the head of the baddest of the bad to write as a convincing killer, so in investigating their cases, I examine sociopaths from their childhoods, through their crimes and into the confessions and jail terms, to try to understand what makes them do what they do. It’s not true that all criminals are sociopaths, but sociopaths make up a heavy majority of prison inmates and violent offenders.

In truth, research on sociopaths is in its infancy, and diagnosis is extremely difficult, not helped by the fact that sociopathic patients are very good at mimicking the traits of non-sufferers. The condition (which is referred to interchangeably as psychopathy, if the term can be removed from what pop-culture did to it) is a spectrum disorder that can be as subtle as it can be bleedingly obvious (no pun intended). So the most interesting way to apply an understanding of the condition is to have a look at its nuances represented in people whose diagnoses we have no doubt about: serial killers.

If research into sociopathy/ psychopathy were a tree, somewhere at the base of that tree would be the research of Dr Robert Hare. Hare devised a ‘checklist’ of behavioural traits we can apply loosely to serial killers to try to understand what made them do the terrible things they did. There are 20 points, including glibness or superficial charm; a grandiose sense of self-worth; a constant need for stimulation or proneness to boredom; pathological lying; conning or manipulation; lack of remorse or guilt; a shallow affect; callousness or a distinct lack of empathy; tendency toward a parasitic lifestyle; promiscuous sexual behaviour; early behaviour problems; lack of realistic long-term goals; impulsivity; failure to accept responsibility for one’s own actions; many short-term marital relationships; juvenile delinquency; and criminal versatility.

A clinician generally scores the patient with zero for ‘no presence’ or two points for ‘definitely present’. The average person scores five or below, with psychopaths scoring 30 to 40 points.

Between 1989 and 1990, Aileen Wuornos shot dead seven men on Florida highways after taking rides from them obstensibly to offer sexual services. Wuornos had begun her life as a prostitute devastatingly early, offering sex for cigarettes, drugs and food at the tender age of 11. She grew up the victim of repeated sexual violence and by 18 began appearing on criminal charges ranging from driving under the influence to firing a handgun at a moving vehicle.

Wuornos received a Hare-style assessment and scored a 32, which puts her in the lower category of definite psychopath, while still being a dangerous individual. We have to wonder if she hadn’t suffered such environmental influences as a child, whether she would have committed the crimes she did. During her trials, Wuornos wavered between fabricating extremely graphic depictions of the attempted rapes and beatings the men she killed inflicted upon her, forcing her to kill them in self-defence, to flat- out admitting she killed out of hate.

In a petition to give up all pending appeals submitted to the Florida Supreme Court in 2001, Wuornos stated: ‘I killed those men. Robbed them as cold as ice. And I’d do it again, too … I’m one who seriously hates human life and would kill again.’

Wuornos certainly exhibits Hare’s parasitic lifestyle — she would live on the money and drive the cars she stole from the men she killed. We could not accuse her, however, of having much superficial charm. She was by all accounts abrasive, quick to anger and difficult to befriend. It’s hard to imagine a woman who wandered the rainy, windy roadsides for hours on end thumbing rides for sex as having a grandiose sense of self-worth, or indeed, the inability to endure boredom.

Dennis Rader, the self-proclaimed ‘Bind, Torture, Kill’ murderer of Sedgwick County, Kansas, is closer to the perfect- score psychopath. An over-zealous dog catcher and compliance officer, Rader thrived on fining people for letting their lawns grow too long or walking their poodle off its leash. Strutting his stuff as a law-man, Rader fulfilled elements of the psychopath checklist that are the domain of the profoundly common ‘business’ or ‘pro-social’ psychopath. Self-worth: high. Empathy: low. But, defying the sexual promiscuity and proneness to boredom that forces so many psychopaths in and out of turbulent intimate relationships, Rader was happily married, with glorious children and an immaculate suburban home. His wife and kids were shocked when he was arrested for the brutal slayings of 10 people, with unknown and undiscovered victims suspected by police.

Rader’s youngest known victim was nine, and his oldest, 62. He wiped out most of a family on a sunny morning at 7am, while some of them were eating breakfast. And, unusually for serial killers, Rader’s murders came with significant gaps, the longest eight years, defying the need for stimulation and propensity for boredom of his psychopathic bretheren. On one hand, he displayed the kind of patience required to stalk potential victims for years at a time. Yet, lying in wait in 63-year-old Anna Williams’ darkened home, Rader became so frustrated when she failed to return from an evening with friends that he up and left. Williams only learned later what Rader had planned for her, after he confessed.

Ted Bundy, the posterboy for serial killers everywhere, is by far the closest to the perfect 40/40 score. Bundy confessed to the murder of 30 women and girls between 1974 and 78, but published estimates run as high as 100. There are theories about Bundy’s involvement in the disappearance of an eight-year-old girl when Bundy was 14. A charismatic, handsome and much- loved law-student in and out of studies at different institutions, Bundy’s penchant was for beautiful, successful brunettes with their hair parted down the middle. So intriguing were his performances while representing himself at his murder trials, young women started turning up to make eyes at him from the gallery, their dyed brown hair parted down the middle.

On one end of Bundy’s personality, he maintained a warm friendship with crime writer Ann Rule, who would sit beside him as they volunteered on suicide hotlines. Tirelessly saving the lives of strangers is an activity which no doubt would require a tremendous amount of genuine empathy or an incredible ability to mimic it. Bundy would walk Rule to her car at the end of the night to make sure she got out of the parking lot safely, warning her that there were dangerous men out there. At the other end of Bundy’s personality, far into the reaches of the darkness, this man would rape and bludgeon women and girls to death and hide their bodies in the wilderness. He would re-visit the bodies, sometimes up to a year after the crime, to paint their faces with make up, change their clothes, and violate their corpses. He blamed his dark side on exposure to violent pornography when he was a kid. To Bundy, he was a victim, too.

The only thing that might consolidate these two vastly different halves of the same man is a whole lot of acting. And that’s what’s most terrifying about psychopaths. They’re great actors. The smile that Wuornos gave those drivers as they pulled aside her on the highway. The cheerful knock of Rader’s fist on the front door. Bundy’s exhausted wink from across the call centre as he listens on the phone. These are the masks they wear, and there are so many different ones. If the writers of Sherlock think the world should fall in love with sociopaths, they’re dead wrong.

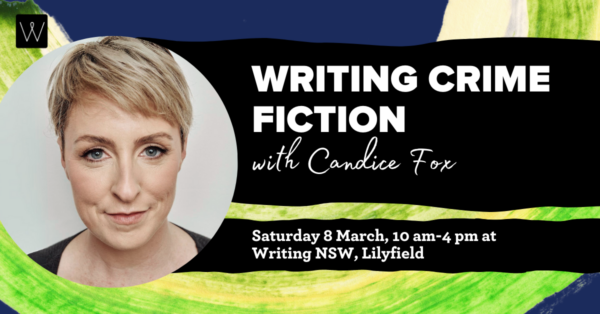

Candice Fox is the author of eleven crime novels and the winner of three prestigious Ned Kelly Awards. She has also co-written seven New York Times bestsellers with James Patterson, the world’s bestselling thriller writer.

Candice’s novels Crimson Lake and Redemption Point were adapted into a major ABC TV series called Troppo.

A meticulous researcher, Candice has interviewed a serial killer on Death Row, been to prison three times (for work purposes) and while on honeymoon in the US took a road trip to famous crime scenes looking for clues. She has also dined with a former President of the United States, filmed a cameo role in her latest screen adaptation and, as a volunteer for WIRES, has rescued countless wild animals. She lives in Sydney.

Join Candice’s course, Writing Crime Fiction, on Saturday 8 March 2025. Enrol here >>