‘Resilience’ is all the rage, by which I mean it is a word with currency in the contemporary landscape. It’s a word that is often coupled with suffering and summoned concerning traumatic experience. It’s a problematic word, or rather, it’s a word that is often used in problematic ways. Let’s begin with the basics. The Macquarie Dictionary uses words like power and elasticity, rebound and recoil to describe resilience, finally declaring it the ability to recover readily from illness or depression etc. It also evokes buoyancy and cheerfulness, though cheerfulness in the face of life’s curveballs might, frankly, be a stretch.

Resilience is about more than just survival. It’s about the capacity to bounce back, to continue to evolve despite obstacles or hardship. Most people think of it in individualistic terms. Therein lies the first problem because in this casting the onus is firmly placed on individuals to endure and prosper despite adversity that sometimes results from inhumane and inhospitable social circumstances. Reckoning with life’s ups and downs, with trauma and grief are inherently solitary and lonely to some degree, but when I think of resilience, I think of community. I think of all the help I’ve had along the way. I might have had some inherent strength and tenacity, but I’ve also been schooled on how to be resilient. Resilience at its most robust is about thriving, even when the odds are stacked against you, but it doesn’t mean you get to be superhuman or avoid fragility and distress. At the bottom line, it means that when you get knocked down, you’re able to, at some point, get back up again. But there are qualifications.

The Problem with Resilience

Questionable applications abound, as Parul Sehgal points out in The New York Times Magazine. Sehgal writes that resilience is ‘indistinguishable from class American bootstrap logic when it is applied to individuals, placing all the burden of success and failure on a person’s character’. Snowflakes. Cancel culture. Social Justice Warriors. It’s easy to dismiss valid objections and activism as whiney or demonstrating a lack of grit, and such dismissals often show up on class, gender, race, and generational fault lines. Using resilience to praise people who survive genocide, systemic racism, and other social ills in place of addressing the cultural drivers and holding perpetrators to account, is loaded. When we privileged white people use this word, we must remember that resilience is not an even playing field, to trot out the kind of cliché we writing teachers are practised at picking up. It can be hard to get back up again when an entire social structure is holding you down.

As Vinita Srivastava points out in an article titled ‘Don’t Call Me Resilient’, labelling marginalised people as resilient ‘has other implications’ – especially when it is policy wonks doing the labelling. ‘The focus on resilience and applauding people for being resilient’, she states, ‘makes it too easy for policy-makers to avoid looking for real solutions.’ Such a take on resilience is a cop-out, a way to deflect social responsibilities and leadership failures, a strategy for masking racism, sexism, ableism, ageism etc. It places the burden of resilience on particular, structurally disadvantaged individuals and communities rather than redressing social injustices and inequities.

Resilience is not the same as denial, and it’s not about disregarding being victimised or minimising injury. If there’s a human rights violation, there’s a human rights violation. If there’s a setback, there’s a setback. If you’re being exploited, you’re being exploited. If you’re wounded, you’re wounded. If there’s grief rising to the surface, there’s grief. In my experience, the willingness to meet vulnerability and stay with it, witnessing to it and perhaps allowing trusted others to witness to it, the willingness to accept help when needed and seek out resources is the crux of resilience, the fuel of it. This is how I’ve forged the kind of life –not despite trauma, but through it – that some people might consider admirable.

But I’m wary of self-congratulation when it comes to talk of resilience. Overcoming or learning to live a fruitful life given realities like discrimination, mental health conditions, or physical illness is not about being smart or strong (though it does require some courage to stay the course). And falling prey to those effects/affects isn’t about being foolish or weak.

Resilience is not a moral issue. I don’t know if I could make any claim to resilience if I had come out of a concentration or refugee camp or lived in indefinite detention or a hotspot like Palestine, West Papua, or COVID-ravaged India. That order of trauma might have broken me in ways I couldn’t come back from. Resilience is not a badge you get to flash to prove you’re better than someone who is sinking. We might like to think of it as an internal muscle of fortitude we can flex as needed, but neuroscience suggests it’s more complicated and less egoistic and romantic than that. Apparently, it all comes down to your window to stress arousal.

The Window

Professor Elizabeth Stanley outlines how the width of your window to stress arousal determines your resilience capacity in her Mindfulness-based Mind Fitness Training. According to Stanley, our windows are created in childhood and can widen or narrow throughout life. You can mindfully widen your window to stress arousal; it’s not fixed; resilience is an active process. You can lose as well as gain it. It all depends on how the stressors are weighted against existing resilience. The wider the window, the better we cope with challenging or threatening events. Having a narrow window makes us more likely to habitually compartmentalise feelings, sensations, bodily needs and limits, more likely to let emotions drive decisions, and more likely to develop Post-traumatic Stress Injury following a potentially traumatic experience. As Stanley puts it, the part of the brain known as the survival brain is automatic and unconscious, unlike the ‘thinking brain’, which operates as an executive function. Unconscious threat perception in the survival brain triggers stress arousal. It codes implicit memory and generalises based on that to anticipate future threats, which is why people who have already experienced trauma and who have not sufficiently recovered generally have lower stress tolerance, often leading to chronic stress. The survival brain does not relax its grip on threat perception, allowing stress arousal to return to baseline and the thinking brain to come back online unless it perceives safety. Safety and support are, therefore, crucial to optimising resilience.

Even so, a degree of mystery continues to surround resilience as researchers struggle to understand why some people seem more resilient than others given similar life conditions and experiences. Maria Konnikova teased out the evidence in The New Yorker, stating that researchers determined that a consistently high resilience capacity involves two key factors: disposition and luck. Being lucky, in their terms, means having at least one loving and supportive caregiver bond in childhood. Having a resilience-friendly disposition means having a ‘positive social orientation’ and an ‘internal locus of control’, a sense of agency. Perception, then, is key to whether a potentially traumatic event or stressful event overwhelms the capacity for resilience, which brings me back to my point about community and the importance of support. For those of us not blessed with a resilient-friendly disposition, the pressure is on to learn the skill of ‘reframing’, which, in psychological terms, means intervening on a thought pattern or conclusion to look at the situation or event from a different perspective, which in turn changes its meaning. And it’s not always easy to do that in isolation. As Dr Brock Bastian makes clear, reframing is not about positive thinking, but it can make it possible to shift how we view and feel about our experiences. And it can calm the survival brain’s fear-based acuity and reduce stress arousal.

Resilience and Writing

Writing can be a way of reframing. Undoubtedly, writing is a way of making sense of things, of exploring differing perspectives. It can be a way of connecting with agency, especially when it comes to writing memoir or drawing on lived experience in fiction writing. Resilience is not the same as catharsis – the process of releasing intense or repressed emotion – though it can bear some relationship to it.

People often assume writing Traumata was a cathartic experience for me. The idea here is that it perhaps helped me come to terms with my traumatic history, and thus writing the book became a resource for resilience-building, but this is not quite the case. Though I found writing Traumata highly emotional at times, I didn’t find it cathartic as such. It likely worked the other way around; I was able to write the book because I had developed enough resilience to go back into that history in a sustained manner. In other words, writing and resilience are a two-way street. It is possible to write yourself into increased resilience. But often enough, we need that resilience in place before we can face writing a challenging work, especially when it mines painful personal experience.

What does it mean to be resilient as a writer? It means learning how to weather rejection and showing up to write again. It means being able to accept the ‘failure’ of certain pieces or projects and moving on to start another. It means finding a community that helps regulate stress as you hone craft skills, whether that’s a short-term community, like a Writing NSW writing course, or a long-term community like an ongoing writing group. It means widening that window of stress arousal in your writing practice. It also means making considered choices about what to write and when. Postponing writing about something that you feel you cannot (yet) face is not a sign that you are resilience poor. That’s self-care and knowing your limits at a given point in time. It’s a sensible strategy.

Ultimately, the relationship between writing and resilience has, for me, been less cause and effect and more like a complex interweaving. From the tender young age of 14, writing has given me the desire to keep going, a way to move through what I experience and what goes on in this world, a way of grappling with it, a pulse of connection to myself and others that is available anytime and anywhere I can write. That pulse of connection has been my lifeline.

Writing has both tested my resilience and taught me resilience. And, perhaps most importantly, through the process of reading and writing, we can develop networks of community with like-minded others that give us spirit and heart and help us forge that potent mix of pliancy and hardiness so vital to being a long-haul writer.

Commissioning editor: Kirsten Krauth

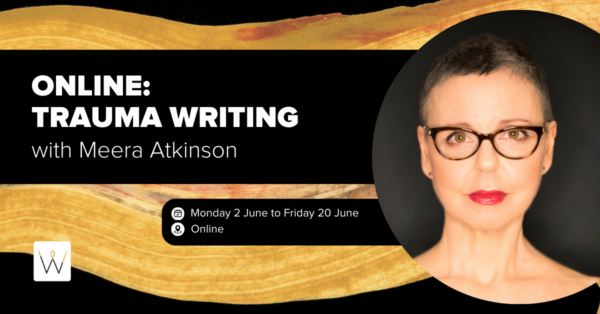

Meera Atkinson is the author of Traumata and The Poetics of Transgenerational Trauma. Her creative nonfiction, fiction, and poetry have appeared in many publications, including Best Australian Poems, Best Australian Stories, Griffith Review and Southerly. Meera has over a decade of experience teaching writing in university programs and as a private mentor.

Enrol now in Online: Writing Trauma with Meera Atkinson, Monday 2 to Friday 20 June 2025, online.

If you want to be the first to read great advice, prompts and inspiration from our incredible tutors, subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter Newsbite.

More from Writing NSW

Check out our full range of writing courses in Sydney, our online writing courses and our feedback programs to see how we can help you on your creative writing journey. Find out about our competitions and opportunities, as well as writing groups across NSW, and sign up to our weekly newsletter for writing events, opportunities and giveaways.